Sunday, August 13, 2006

My Road by Jason Pisano

Published: Sunday, July 4, 1999 Edition: STATEWIDE

Page: 8 Type:

Section: NORTHEAST Source: JASON PISANO

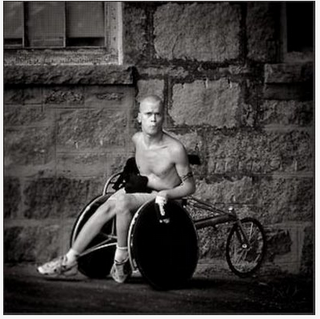

Photo by Derek Dudek www.derekdudek.com

MY ROAD

MY LEFT FOOT SERVES AS MY TWO HANDS. IT'S PROPELLED ME THROUGH THE BOSTON AND NEW YORK MARATHONS.

I HAVE A STORY THAT SHOULD BE OF USE TO THE ABLE-BODIED. AND I WANT TO INSPIRE.

I am a 27-year-old newspaper reporter, a graduate of the University of Connecticut, where I majored in journalism, and a marathon runner. I have had more obstacles than most students in the way of achieving my goals.

I was born with cerebral palsy. I have no use of my arms. My condition also affects my speech, making it very hard for me to communicate with other people. One of the main ways that I overcome these disabilities is by developing the use of my left foot. I use my left foot to change the television station, turn on the radio, even type an article such as this one.

Most ``normal'' people do not have any idea how difficult an average day can be for an individual with multiple handicaps. Just imagine having to depend on another person to do almost everything for you, including feeding you, bathing you, folding or unfolding a wheelchair every time you get in or out of a car, or just helping you get into your wheelchair. The only positive thing: The damage to my brain does not hinder my mental capabilities.

I wrote this story in hope of inspiring: inspiring the young, the old, the disabled and the able-bodied. After seeing the movie ``My Left Foot,'' my aspirations to write my story escalated. ``My Left Foot'' is about an Irish man, Christy Brown, who also had cerebral palsy. The major similarity between Christy Brown and me is that we each use the left foot to accomplish tasks for which other people would use their two hands.

From the day I was born Jan. 25, 1972, in Cranston, R.I. I have had to fight against the odds. When my mother went into labor there were two days of complications. When I was finally delivered, I had the umbilical cord wrapped around my neck, double pneumonia, and weighed 12 pounds. It was touch and go for a week; the doctor said I had a 50-50 chance of surviving.

I had to stay in the hospital until I got well enough for my parents to take care of me. After about three weeks, I was released with a clean bill of health. Six months later, my mother realized I was not progressing as I should have been.

She took me to several doctors, but they could not find anything wrong with me. Finally she took me to Dr. Eric Denhoff. When my mother entered the office with me in her arms, he took one look at me and said that I either had a brain tumor, epilepsy or cerebral palsy. The first two of these would be fatal, he said.

It turned out to be cerebral palsy. My brain had been starved of oxygen when the cord was wrapped around my neck. The cerebral palsy left me unable to walk, and with a severe speech impediment which makes it hard for me to be understood.

When I was 6 months old, I went to a baby program at Meeting Street School, a special school in East Providence for disabled children. When I was ready for school, I remained at Meeting Street, which emphasized physical therapy instead of academics. I knew that the day would come when I would have to leave and try to make it in the real world.

By the time I was 12, my mother knew that I needed to attend a public school where I could get a chance at a so-called ``normal education.'' So I was enrolled as a fourth-grader in Maisie E. Quinn Elementary School in West Warwick. In the months leading up to my leaving Meeting Street, my mother was warned numerous times that I would probably be at the bottom of the class and end up back at Meeting Street.

When I first arrived at Quinn I was nervous. The schoolwork was the least of my problems. Trying to adapt to a regular school was a far more difficult task. At Meeting Street I was parked in one classroom all day. At Quinn we had recess, lunch and gym. I can recall my first recess; my aide brought me out to the playground and pushed me around the yard with a bunch of girls giggling and chattering all around us. I prayed that the period would end.

This continued for about a week until one day we were walking by some kids playing kickball. I really wanted to play, so I asked my aide to ask them if they'd let me try to kick the ball.

My first kick, which went over the pitcher's head, was my ticket to popularity. After a few weeks of learning about my abilities, these kids were coming up with rules to make me be an equal.

If a fly ball hit me while I was in the outfield the kicker would be called out. This rule made me a highly popular pick when it came time to choose sides. Now recess was not something that I dreaded, but the thing I most looked forward to.

During one recess, I almost died. It had rained the night before and the playground had big puddles. One of my smaller friends was pushing me around the kickball bases when one of my wheels got stuck in a sewer grate. My chair tipped over and I fell, my face submerged in a puddle. If one of my bigger friends, Jason Lombardi, hadn't raced over and picked me up I could have drowned.

My relationship with the kids at school continued to grow in as well as outside of school throughout my first year. Some of the kids got really close to me, sometimes even spending whole weekends at my house. Towards the end of my first year at Quinn some of the kids began to understand me and tend to my needs better than my aide and my teachers.

This was also the time in which I developed my first relationship with a girl. I was 13 when I met Kerry. It was a spring afternoon. I was playing with my friends at recess as I had been doing all year, but then it happened. As I was waiting for my turn at bat, I caught a glimpse of this pretty little blonde girl. For the next three weeks she was all I could think about. Finally, I asked one of my friends to ask her what her name was. Of course I already knew her name, but I needed a way to meet her. My friend did what I asked him to do, and a few minutes later I was talking to her. Or was trying to. One of the most frustrating things about my condition is the fact that when I become excited, happy, mad or sad my disability shows more, so it's extremely difficult for me to make myself understood.

As I saw her coming over to me I immediately felt my whole body tighten up. I kept telling myself to try to relax, but it was no use. I was too excited. By the time she walked over to me I was so tight that I could barely open my mouth to say hello. I know she must have been a nervous as I was, but she hid it well. This first impression probably would have scared off a lot of other 10-year-old girls, but not Kerry. She was beautiful, and she was immediately my most special friend.

My relationship with Kerry grew throughout the next couple of years. We would go out on the weekends to the movies or bowling, and spend all of our recesses together. It seems funny to me now how easily Kerry adjusted to my disability. She would hold my foot, instead of my hand.

When my parents got divorced I was 15 and in the sixth grade. Kerry helped me through that difficult time. My grandfather died the following summer. Kerry was there for me once again. Kerry seemed like the only person I could talk to and rely on.

But when we reached junior high, we were placed in different classes and began to meet different people. We spent less and less time together. We eventually ``broke up,'' though we remained friends. Losing Kerry as a major part of my life made junior high very difficult.

The first few months in junior high were once again an adjustment. There were kids from other grammar schools who had never seen me or any type of disabled person before, and did not know how to treat me. But this time it was not nearly as hard for me to gain acceptance as it had been in grammar school, because I had some friends to teach the others about my disability and because I had a lot more confidence. I talked to a lot more people. I was no longer afraid that I would be made fun of.

All this time, my mother and grandmother did everything possible to enable me to make my dreams come true. My mother always stressed how important it was for me to get a college education; she explained to me how other kids would be able to go out and get any kind of job. But because my disability left me unable to use my arms I would not have that option.

``You can't go out and flip hamburgers at McDonald's,'' she would say. I used to hate it when she said this, but now that I am older I am grateful that she pushed me so hard.

While my mother was busy keeping my nose in the books, my grandmother was thinking about ways for me to live a so-called ``normal life.'' She would spend days on end adapting ways for me to do things that other kids my age were doing.

I can recall a particular day when she cut a hole in a Wiffle Ball so I could put my toe in the ball and pitch it. Another time, she taped a hockey stick to my leg so I could play with the kids in her neighborhood. My grandmother was determined to make my childhood as normal as possible.

In eighth grade, I played handball, a cross between football and basketball played in wheelchairs. I had an accident that caused me to have major surgery on my hip. What was supposed to be only eight weeks out of school turned into seven months at home in bed because of an infection acquired during my stay at the hospital.

I decided not to let this setback prevent me from graduating with all of my friends. So when I returned to school I had a great deal of work to make up. I was determined, and with the help of my teachers I was able to catch up with my classmates.

Going into ninth grade I felt kind of left out because all of my friends were trying out for sports teams. I watched my friends getting dressed up for football practice, and thought: I would give anything to just be able to play for just one day. For someone who loves sports as I do, it was very frustrating and difficult to deal with. I had my own teams, but they were not part of school life and only involved other disabled kids. Sports teams are not just about what happens on the field; they are about the feeling a kid has about being a part of a group of children representing his school.

I also had to deal with the social issues that arise at this age. Most of my friends were beginning to date. This made me feel a little left out, but I thought I could cope. That was before I saw her.

It was a Friday afternoon and school was just getting out. I was staying after school to watch a basketball game, when I glanced out the window and saw Kerry getting into a guy's car. I stayed for the basketball game, but my mind was on other things.

In the summer of 1989 I competed in the New England Track And Field Championships in Hartford for people with cerebral palsy. I won four gold medals.

I raced with people who raced the same way that I have to: backwards in a wheelchair, only using my feet. I won the 100-, 200-, 400-, and 800-meter dashes. This was the first time I had ever won a race at such a big competition. After I returned from the meet, there were several articles about my achievements in the local newspapers.

A few weeks later I returned to school for my sophomore year. My homeroom teacher, Mr. George Coombs, was one of the track coaches. He heard about my accomplishments over the summer and asked me if I would be interested in practicing with the high school team. For the rest of the day I could not think of anything else. When I got home from school that day, I could not wait to tell everybody the good news.

When I got home my mother could hardly figure out what I was trying to tell her. When she finally got what I was saying, she was very happy. I knew I would not really be competing with the other kids, but just to be part of my high school team was enough for me. It seemed that spring could not come quickly enough. I could not wait to show the kids that I was an athlete, too.

Spring finally came, and the first day of track practice. I knew a couple of kids on the team, but I was still nervous. As we were warming up, something happened to break the ice. Stretching my back, I leaned forward and ended up tipping my wheelchair over face-first. Everyone busted out laughing, including me. I remember thinking; ``This is great, only I could tip myself over before practice has even started!''

In the following weeks I would make a lot of friends on the team. John Gallo became my best friend. John was captain of the football team and very popular. I met him about a month before the track season opened, when the football team came to play my wheelchair handball team in a fund-raiser.

That game is still fresh in my mind. My coach made the football team get in wheelchairs and tape either their hands or their feet to their chairs, so it would be a fair game. From the first whistle I knew whom I was going after: the biggest guy on the team, John.

For the rest of the game John and I were bumping and ramming one another. By the end of the night, when we were finished beating up each other, we found that we had developed a friendship.

As the track season went on, John began working for me as a Personal Care Attendant, or PCA. This surprised a lot of people who knew him. In the past he had been known as a tough guy. Nobody would have ever thought John would take an interest in a disabled person. It wasn't that he was a bad person, but they thought that he lacked the patience needed to be a friend to somebody with a physical disability. Teachers were amazed at how much time John was spending with me. Whether he was going to the movies or just hanging out with the guys, John was always willing to take me along.

Later that spring John graduated from high school and decided to join the Marines. But before he left, we had a goal to accomplish. I had told him that I'd always wanted to finish a road race, but had never pushed myself even a mile before. John told me that we were going to train until he felt that I was ready for one. After a couple months of working out we set our sights on the Downtown 5K, in Providence.

It was a cold October morning in 1991 as we headed out to the race with our hearts filled with determination. If we started, we were going to finish, he told me.

All 3,000 runners and a couple of wheelchair racers passed us by the first half-mile. It did not matter to us. We were just worried about finishing the 3.1-mile course. He kept encouraging me to keep focused on our mission. About 2 1 >12 hours into the race, we had only a half-mile to go. My legs were hurting and my hip was in severe pain, but none of this was going to keep me from the finish line. With my best friend at my side, I crossed the finish line about two hours after the last runner.

That night I received a call from a sportscaster named Ken Bell. He said he had seen me on the videotape of the race and could not believe his eyes. He asked if he could come out to my house and interview John and me. I agreed. He came the next day and spent a couple of hours with us. In the following years, he has always followed my racing career.

After completing this race, I knew it was in my blood to do marathons. I then thought how I could do better. I heard about a man who used to race in a wheelchair and now custom-built racing chairs. I knew this would be a challenge, because my chair had to have the standard three wheels but the seat had to face the opposite way, so I could push backwards with my legs. On a cold, crisp day in May 1992, I pushed myself six miles around a track to attempt to raise the $3,000 that I heard it would cost. I was successful, thanks to many friends and strangers who sent donations.

I still remember the incredible feeling I got when I sat in this lightweight racing chair. This was the turning point in my career: I knew if I could raise the money to buy my chair, I could achieve anything I put my mind to.

When John left for basic training, I figured that I would never find a friend as dedicated as he was. For the next month I spent a lot of time looking for a PCA until I remembered a guy that John had introduced me to a couple of weeks before he left.

His name was Lonnie Morris, an ex-football rival of John in high school. Lonnie worked on a lemonade truck during the summer. One day, as John was taking me home from the gym in his car, we had stopped by the truck to say hi to Lonnie. All the time John was talking to him, Lonnie was staring at me. He finally asked John who I was. At first Lonnie was uncertain whether I could understand him, but after John explained about my disability he began to talk to me as an equal.

So now, after a month of unsuccessful searching for a PCA, I called him up and asked him if he was interested in working for me. He came over to my house a few times to get to know me better, and shortly afterward, he took the job.

Lonnie was very different from John. Lonnie liked to try to help everyone. Street people, alcoholics Lonnie thought that he could do something to help them. He was the kind of guy who thought he could change the world.

The only problem with Lonnie was that he was too protective of me. He was always afraid that someone or something was going to hurt me. Every time I would go out with a girl, he would take her aside and ask her about her intentions. This really irritated me. I tried to explain to Lonnie that everybody gets hurt sometime in life; me being in a wheelchair does not mean that I should not experience everything that normal teenagers go through. It took Lonnie months to understand what I meant.

My senior year in high school was my best year. I had more friends than ever. I was looking forward to applying to colleges, but was in no rush to leave. I wanted to enjoy my last year with all my friends. From football games to parties, I had the time of my life.

The end of my senior year brought a dilemma: the senior prom. I really wanted to go with Kerry, but I knew she had a boyfriend. I decided to ask her anyway. Just as I suspected, she said no; she was going with him. I was a little disappointed, but I wanted to go anyway. As luck turned out, I met a girl named Kelly at a party. We went out a couple of times and I decided to ask her to go to my prom. She said yes, but I found out few days later that she had also said yes to three other guys.

This made me a little upset, so I called her up and canceled, which left me once again without a date. As the prom drew closer, I decided to try one more time.

I was in gym class when I saw this beautiful girl with blonde hair. After thinking about my options, I decided to write her a note asking her to go to the dance. The only problem was that I didn't know her name. I just gave her the letter without a name on it, and waited for a reaction. It was a couple of weeks and I still had not heard from her; I figured she was not going to go. Then one day after track practice, a kid came up to me and said, ``I heard you are going to the prom with Rochelle.'' It was not until this time that I learned her name. He gave me her number and I called her and made a date to get to know her.

We went out every weekend for about a month and a half before the prom. We got to know each other well and looked forward to the dance. Around a week before the prom, Kerry had a fight with her boyfriend. I knew if I asked her she would go to the prom with me, but I knew I could not do that to Rochelle.

Prom night came and we were getting ready at my house. A knock on the door came and it was Kerry. She said she wanted to see how we looked. I was happy to see her, even though she was not my date. I always wonder: If I weren't disabled, would Kerry and I have ended up together? I try not to think like that, but sometimes I can't help it.

I had a good time that night. We danced a lot. This was accomplished by Rochelle sitting on the pad in front of my chair while I pushed us around the dance floor with my feet. When I wasn't dancing with Rochelle, my friends and I were sneaking in the bathroom to drink shots of Southern Comfort. This made me loosen up, literally, and allowed me to have a better time. The night was great, but I still wished Kerry were there with me.

After the prom, we went in search of a party we had heard about at a hotel, but could not find it. We took her home. I kissed her goodnight and she got out of the car.

I proceeded to get sick all over the car. I guess I had had a little too much to drink.

Before I knew it, it was June 12, 1992, high school graduation day. As my mother was putting my cap and gown on, I remembered all of the hard work that my family and I had gone through to reach this day. I was proud of myself and grateful to have such loving people in my life.

As we arrived at the procession, I began to get excited; I could not wait to see my friends. As my name was called, I could hear people cheering. I looked over at my family and saw the emotion on their faces. All the hard work that I had gone through was worth it, at that moment.

In the fall of 1992, at the age of 20, I began my freshman year at the University of Connecticut. My friends and family did not understand why I had picked a school out of state. They had many doubts that I would be able to function and live on my own in a dormitory. I do not really know why I wanted to go away to school, it was just something that I felt I should do to see if it was possible.

When I arrived on campus in late August, I was surprised to find out that I had a roommate. Even more shocking, he had no idea he was rooming with a multiple-handicapped person until I arrived at his door.

His name was Charlie; he was a senior and about five years older than I was. He had never known anyone with a disability before. At first he was hesitant to talk to me because he was afraid that he would have trouble understanding me, but after a few weeks we got to know each other and became friends. Charlie even worked all of the overnight PCA shifts for me.

I had been used to having my mother or my grandmother around me to take care of my every need. Now, I was forced to become more independent and have more patience. These two improved aspects of my personality would not have come about if I had never left home. With PCAs not always available, but the need for bathing and feeding always there, I had to learn quickly how to manage my time.

It was not always smooth sailing in the beginning. One time when Charlie was helping me with the urinal his hand slipped. Needless to say, both Charlie and I had to take a shower.

The other difficult adjustment was in the classroom. In high school I had graduated 33rd out of 166 students. When I got to college, I figured I would be able to take five classes and get all As, but this was not the case. The first semester I started out with five classes. And after the second week of school, I dropped three of them. Even worse, I got a B and a C in the two remaining classes. Bs and Cs are not that bad, as grades go, but when you only take two classes, you expect better. I had never had to worry about my grades before.

My racing took a back seat for my first year at college. I had to realize that school came first, but I knew that once I got control over my studies and social life, I would find time for my sport.

My second year at UConn I met a new PCA, Randy Spellmen. He answered an ad at the disability office on campus and came to my room to meet me. He asked a few questions about my disability and, shortly afterward, he took the job. He was the preppie type who studied all the time; I really did not think we had much in common. I thought of myself as a jock who would rather work out than study.

As I got to know him better, he began to loosen up. We began to spend a lot of time together at school, as well as at my house in Rhode Island. I remember the first time I took Randy to a bar. It was a neighborhood bar in Rhode Island. My mother dropped us off and picked us up. Randy was only 19, and never had a beer before. By the time we left the bar, he looked like he had a disability. When we got home, it was snowing out. Randy got undressed and went out in about a foot of snow, dancing in his Reindeer boxer shorts. This was the start of a great friendship.

That spring Randy, Ray a friend from home and I decided to take a bus to Daytona Beach for spring break. This seemed like a good idea when we talked about it, but the bus ride was from hell. The bus driver hated college kids, we got lost on the way and we got a flat tire. We finally arrived in Florida after about 26 hours of non-stop ride.

But as horrible as the ride was, it was well worth it. Spring break was awesome. We met a lot of people from all over the country. Because Randy did not have a fake ID, we were forced to drink in the room before we went to the clubs at night. Randy and I got into a huge argument with a convenience store clerk; he would not sell me beer because I was with a minor. After a few obscene words to the clerk, we ventured out to the next convenience store and got our beer. The week flew by and before we knew it we were back on the dreaded bus.

On the ride home, Randy and I started talking about goals we would like to achieve. I told him that I had always dreamed that I would complete a marathon. He looked at me as if I were kidding. He said that was a long way to push myself. He asked if I thought that I could finish one. I answered immediately; ``You bet your ass I could finish it!''

About six months later I was watching television when I saw an ad for the Ocean State Marathon, which then ran from Narragansett to my hometown of Warwick. I picked up the phone and called Randy. I asked him if he would walk with me. He said he would, but he did not think I would be able to complete the whole 26.2-mile course. I replied, ``You'll see.''

In the weeks prior to the marathon, race officials called me up to try to talk me out of attempting to fulfill my dream. Police threatened to remove me from the course if I obstructed the lead runners. I said, ``Do what you have to do, and I'll do what I have to do.'' My mother told me she did not want anything to do with my participation. She said it was an unnecessary risk to my health, and she would not be a part of it.

On Sunday, Oct. 30, 1994, at 4 a.m. Randy, his roommate Xy Ho and I started our journey from Narragansett to Warwick. I started eight hours earlier than the rest of the runners, and it was chilly and dark. My friend Steve Morriete, who also has cerebral palsy, drove a car in front of me so I would not get hit. In the darkness, we ended up going a mile and half the wrong way. After realizing our devastating mistake we turned around and started back on course.

As the day went along we tried to maintain a pace of a mile per half-hour. As the sun rose, we were about six miles into the race. Previous to this I had only pushed myself a maximum of eight miles. I knew I was going to be hurting. Although it was October, it was very hot. Temperatures reached as high as 75 degrees. At the 10-mile mark I felt weak and almost passed out. I knew I had to stop to eat something or I was not going to finish. After a quick snack I continued on my course.

Twelve and a half hours after we started, we crossed the finish line at Warwick Veterans High School. As I entered the parking lot I saw all of my friends and family waiting for me. Along with them was a television news crew. I cannot put into words what I was feeling at that moment. After so many people had told me I could not finish the marathon, I had proven them wrong.

The next day I was all over the news. The people who had doubted me before were praising me now. Although my body hurt, I felt great. I knew not many people could claim they had finished a marathon never mind finishing one by pushing a wheelchair backward with their feet.

Randy and I decided to set our sights on the biggest marathon in New England: Boston. There was only one thing holding us back: a qualifying time of three hours. We decided to petition the Boston Athletic Association to see if we could have an exception made because of my racing style.

After a few weeks of waiting for an answer I called the BAA. I was given the runaround, and got so fed up that I decided to go ahead and do the marathon unofficially.

About four weeks before the marathon, when I was at school, I received a call from a reporter from the Associated Press. She had heard about my attempts to become an official entry, and thought it would make a good story. She came over to my grandmother's house and spent a few hours asking questions about all aspects of my life. In about a week the story was ready for publication.

After the story about my attempt to be the first person to complete Boston backwards hit the AP wire, I began to receive calls from all over the country. First was a radio station in Texas. Next was a Boston paper. For the next couple of weeks I felt like a star. My phone did not stop ringing at home or at school. By the week of the marathon the pressure was getting to me. I just wanted the day to come.

At 1 a.m. on April 15, 1995, my friends, family, and I got into my van and made the trek to Hopkinton, Mass., the starting line. Waiting at the line were a few television news crews from Rhode Island that would follow me throughout my journey.

I was more focused than I had ever been. I was going to finish this marathon if it killed me. The miles were going by. I knew I was getting closer and closer to my life-long dream.

I reached the 16-mile mark, knowing what was coming up: Heartbreak Hill. This series of hills is about six miles long. It got its name because of the many people who have withdrawn from the Boston Marathon there.

I took some food and water before I attempted my climb. Surprisingly, the hill's reputation was larger than the challenge.

A couple of hours later, I was at the top, and I knew it was all downhill. Nine hours and 50 minutes after my early-morning start, I crossed the finish line in the heart of Boston.

The BAA officials refused to recognize me for my accomplishment, but I felt great and fulfilled. The small crowd at the finish line cheered loudly. As Randy was helping me out of the racing chair and into my other chair, a race official came up to us and said, ``You are going to have to get out of here, only athletes are permitted in this area.'' When Randy tried to explain that I had just finished the race, he replied, ``Sure he did, buddy.'' We wanted to punch the guy in the face. I had just finished nine of the hardest hours of my life and I was not even recognized as an athlete. We decided that it wasn't worth it to let the guy ruin what I had accomplished, and we went home, but I knew that I would be back.

In Rhode Island, people reacted with astonishment. I was praised everywhere I went. People bought me drinks at bars, food at restaurants, and were constantly asking me about my next race. It was great. I felt I had given something to others. I gave others the motivation and ability to push themselves beyond their normal limits.

In the next couple of years, I competed in many races, including two New York City marathons, the Boston marathon again, and most recently, the Walt Disney World Marathon in Orlando, Fla.

Sunday, June 16, 1996, is a day I will never forget. As a ``community hero,'' I had the honor of carrying the official Olympic Torch five-eighths of a mile through Rhode Island.

The previous March, I had been asked to appear at my old junior high school. I showed up at school planning on giving a half-hour speech and leaving. To my surprise they had made the whole day around me, calling it ``Jason Makes a Difference'' day. In the next six months I visited the school frequently, helping lead a fund-raiser walk for hunger.

On June 16, an hour before I carried the torch, a whole bus full of those kids paraded out with signs that said, ``Jason Makes A Difference.'' After I completed my leg of the relay, the kids gathered around me for a picture. If the honor of carrying the torch wasn't enough, these kids surely made me feel like a hero.

Later that same evening, after all the excitement subsided, I sat down to watch the final game of the 1996 NBA Finals. Right before the second half tip off, I had my moment in the national spotlight.

I can still recall the words of the voice in the commercial: ``A lot of people think Jason Pisano should feel bad for himself, but he's too busy doing other things.'' The screen showed me pushing myself backwards with the torch fastened to my racing chair.

A couple of minutes later, my phone was ringing off the hook. One of the calls came from a high school friend, now in the Air Force, named Derick. Derick was always the class clown. He never took anything seriously and rarely let anyone know how he was feeling.

On this night, things were different. His emotions were too much for him to hide. He told me he had seen the commercial, and while we were talking, he broke down and cried.

Later that evening, I went out to a club in my neighborhood. As soon as I entered the place a bouncer came up to me and ask me if I was that guy he'd just seen on NBC. That's when it hit me: the whole country had seen me. Three years previously I was being denied the right to compete in marathons and road races because I was too much of a risk. On this evening, the way that people looked upon me had taken a 180-degree turn. No longer was I pitied or looked upon as being handicapped. I had become a role model and a symbol of what a person can do if they put their mind to it.

As a reminder of that day, I will always have the torch I carried hanging up on my bedroom wall.

On July 18, three weeks after I carried the torch, it arrived in Atlanta at the opening ceremonies. I could not wait to see who the last torchbearer was going to be. I had plans to go out that night, but I made sure I was near a television set. About four hours after the ceremonies began the final torchbearer was revealed. It was Muhammed Ali.

I had loved boxing since I was about 3 years old. I would even put boxing gloves on my feet and box with my father and my friends.

Throughout my childhood Ali had been my idol. When I was 6, I flew to the Superdome in New Orleans to see him fight Leon Spinks and win his title for the third and final time. Ali was my favorite boxer because of his great personality and the confidence that he had in himself.

Training for a marathon is similar to training for a boxing match. Modeling myself after one of the greatest athletes that ever lived motivated me to strive to be the best I could possibly be and not allow my disability to get in my way. Without such a role model, I don't know if I would have ever had the desire or courage to attempt something as difficult as a marathon. They could not have chosen a better and more qualified person than Ali to represent the Olympic spirit.

In the fall of '97, I competed in the Ocean State Marathon for the second time, but this time I wasn't running for myself. I ran for a 12-year-old girl named Rachel, who had leukemia. Earlier that summer I joined the Leukemia Team in Training, a foundation that matches up marathoners with leukemia patients. The runner gets pledges for each mile he runs. I visited Rachel a couple of times over the summer and got to know her. Despite her severe illness, her eyes sparkled and her personality overcame her pale complexion. Her zest for life left me inspired.

In the months leading up to the race, my friends and family raised about $1,000 in Rachel's name. We even had a spaghetti dinner in which Rachel was the guest of honor. I could not wait to see Rachel's face when I crossed that line.

A week before the race I received a call. It was Rachel's mother. She said Rachel's health had taken a turn for the worse. She did not have long to live. Rachel had asked to see me.

The next day I made the trip to her house. The ride only took a half an hour, but it felt like a week. When I finally got to her house, I dreaded going in. I spent a few minutes with her. Before I left, she asked me if I would still run for her, even if she passed away before the day of the race. I told her that I would and she gave me a hug. Six days later Rachel died, one day before the marathon.

On Nov. 9, 1997, in the pouring rain, I completed the Ocean State Marathon in 7 hours and 37 minutes, one of my best times ever. During the entire race, Rachel was on my mind and in my heart. The next day, at Rachel's wake, I presented my finisher's medal to her mother. She thanked me and told me that the medal would always be special to her.

Looking back, I feel fortunate to have had so many loving and supporting people in my life. Without these people, I would not be the person I am today. Even though my life has not been perfect, I would not change a thing. Being born with a disability has presented me with many challenges to overcome. Through accomplishing and persevering over these challenges, I have made my life very fulfilling. I have done more things and gone to many more places than most people will in their lifetime.

Many people who have severe handicaps become bitter over the years. I never have wasted time being bitter. I have always thought I was born like this for a reason. The reason, I feel, is to teach people that life is not always easy and you have to roll with the punches. It is a constant battle and the more fights you win, the happier you are. My philosophy on life is to never give up and to push myself to the limits. In doing this, I hope that I inspire others to live their lives to the fullest.

Both my mother and grandmother have been the base for all the success I have had in my life. They raised me never to feel sorry for myself and taught me that I could do anything that anyone else can do, with a little more time and effort. They gave me confidence in myself. Along with always being there for me they also let me be as independent as possible.

My friends have also played a big part in my life. I have only written about a few but there are many more. These people have gone out of their way to make my life complete and filled with memories. From supporting my racing career to just getting me out of the house to have some fun, my friends have always been there. Without these people in my life, I might not be where I am today.

On May 16, 1998, I graduated from the University of Connecticut with a bachelor's degree in journalism. Two months later, I began working as a freelance journalist. Over the past year, I have written close to 100 articles as a freelance reporter for local newspapers, but I haven't been able to get a full-time position yet.

When I chose journalism as my major, I knew it would be a struggle to find a full-time job, but I decided to go for it anyway. As for the future, I plan to continue to freelance until a position becomes available. I know that it will have to be a very special editor who decides to hire me on a full-time basis. He or she will have to have the vision to see past my disability and judge me on my journalistic abilities.

In my personal life, I hope to be lucky enough to meet somebody that I am compatible with and get married. I know that this will take a very special woman. This person would have to have a lot of patience and accept me for who I am. My mother would say this might happen if I was not so picky. I guess I just am not willing to lower my standards.

As for Kerry, I finally accepted that our relationship is probably never going to be what I had hoped. I used to think my disability was the major thing that was holding our relationship back; now I realize that we are just two completely different people. In the past, I have tried to express my feelings for Kerry in letters, on the phone, and in person. What I finally realized is that a relationship takes two people to work. Even though I had hoped it would turn out different with Kerry, I'm happy that we have still remained friends over the years.

This past year was a memorable one in my racing career. Last November, I completed two marathons in one week, the New York Marathon and the Ocean State Marathon. A short time after my marathon week I injured my hip while training at the gym. This injury was a setback mentally as well as physically. During the three months that I was injured, I had set in my mind that my racing career was over and I needed further surgery on my hip.

In late February, with the help of Jason Almeida, my PCA for the past three years, I began to train once again. My goal was something no one in a wheelchair had been able to accomplish: complete a road race up Mount Washington in New Hampshire.

On Saturday, June 19, I set out. Mount Washington is one of the toughest races in the United States. It is 7.6 miles straight uphill, from the base of the mountain to the summit.

In February, when I contacted the race director, Bob Teschek, he had been opposed to my competing. ``I had a good wheelchair athlete try this race and he couldn't finish,'' he said. That athlete had been able to use his arms. ``This race isn't made for wheelchairs,'' Teschek said.

I didn't take this statement well. I continued to call and argue with him every week for the next two months. Finally, he agreed to let me do the race, but unofficially.

My aide and I searched for the biggest hills in Rhode Island to train on. We found two. We trained in cold weather and hot, in rain and in snow.

The day of the race, I arrived at the base of the mountain with three friends. At 10 a.m. the cannon went off. As I started to inch my way up the mountain, I knew I was in for a challenge. The steepness of the road was something I never had experienced. Because I race backwards, my friends had to guide me around turns with a rope that was tied to the chair, and make sure my front wheel stayed on the ground.

I completed the first mile in 40 minutes. As I began the second mile it began to flatten out. That day was unusually warm 76 degrees at the base of the mountain but I knew I would be cooling off as soon as I reached the tree line.

At mile 3, I drank some water and stretched my back. I was almost halfway in just under two hours.

The next two miles were very steep and mostly dirt. Dirt is a big problem for me, because I have to push off the ground with my foot to propel my wheelchair. My friends took turns facing me, so I could use their feet to push off.

Miles 4 and 5 took about an hour. Although I pushed myself for the entire race, I had to rely on my friends to keep me from rolling back between pushes.

The final 2 1 >12 miles were the hardest. The steepness of the road was unbelievable. I knew I was getting closer to the top, because it began to get cold and windy. The runners who had finished began to come down.

Every hill seemed larger than the next, but with the encouragement of the other runners, I continued.

At 1:45 I reached the parking lot just below the finish line. Only one more hill stood between me and my dream of finishing this race. I paused for a moment; the view was spectacular.

My friends and I took a few big breaths and up we went. Ten minutes later we crossed the finish line at 3 hours and 59 minutes.

So with the help of my friends Randy Spellman, Steve Gallo and Jason Almeida and the grace of God, I became the first person in a wheelchair to complete the Mount Washington Road Race.